Representation of Women in the West Culture and Violence against Women

- Lucie Nechanická

- Jul 20, 2021

- 7 min read

In this article I would like to reflect back on what I have been focusing on during this course and how it affected me when choosing the thopic for my Final Major Project.

Since the beginning of this course I have been researching representation of women in western culture – in the art history and media nowadays, and what impact it has on our society.

I have come across these two terms – male gaze and female gaze. However, before I discuss them I would like to point out what John Berger suggests. In his book Ways of Seeing he argues that historically women have been mostly depicted by a male artist for a male viewer. This hasn’t changed and even nowadays our world is oversaturated by images of women that use the same visual language and are designed to flatter the male audience.

‘In the average European oil painting of the nude the principal protagonist is never painted. He is the spectator in front of the picture and he is presumed to be a man. Everything is addressed to him. Everything must appear to be the result of his being there, it is for him that the figures have assumed their nudity. But he, by definition, is a stranger - with his clothes still on.’

(Berger, 1972, p. 54)

He goes on saying:

‘Today the attitudes and values which informed that tradition are expressed through other more widely diffused media - advertising, journalism, television. But the essential way of seeing women, the essential use to which their images are put, has not changed. Women are depicted in a quite different way from men - not because the feminine is different from the masculine - but because the “ideal” spectator is always assumed to be male and the image of the woman is designed to flatter him.’

(Berger, 1972, p. 64)

Fig. 1: Peter Lely, Portrait of a young woman and child, as Venus and Cupid, 17th century

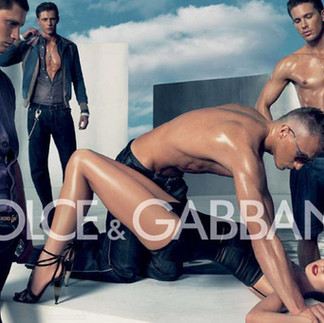

Fig. 2: Dolce & Gabbana, Light Blue

Pleasing the male viewer is strongly embedded in our society. In 1975 the film theorist Laura Mulvey invented the term “male gaze”. In her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema she explains that in Western media the female characters are often depicted from a masculine heterosexual perspective. They are not necessarily objectified (even though in most cases they are), but rather viewed from a limited male perspective and their role is narrowed down to serve the male protagonist’s interests and storyline.

Fig. 3: Transformers, 2007

However, the female gaze is a new term. Stefani Forster explains in her essay:

‘The “female gaze” is not about asserting female dominance on-screen. And it does not mean that therefore we get to “man-jectify” men in reverse. [Female gaze] is about making the audience feel what women see and experience. ‘

(Forster, 2018)

Studying my photographs more closely I have realised an interesting reality about my work. Despite of being a woman who is in charge of the camera I have turned myself into an object of male gaze many times. How did it happen? I believe that the unconscious consumption of images that surround me every day (ads, fashion magazines, photos on Instagram, music videos, films, etc.) plays a big role here. I have subconsciously applied the same visual language I had learned from these images into my own work. I have never questioned where my ideas for poses were coming from because they felt so natural. But the reality is they are not – they were invented by someone else for the consumption of others – usually men. (I will write another article where I explain it in detail.)

Fig. 4: Lucie Nechanicka, Untitled, 2020

Fig. 5: Lucie Nechanicka, Untitled, 2020

Sut Jhally explains in his film Dreamworld 3: Desire, Sex in Music Videos:

‘The question is not whether the images are good or bad. The question is whose stories are being told, through whose eyes are we seeing the world, who is behind the camera, and whose fantasies are these?’

(Jhally, 2007)

The women are often framed to be viewed as an object to be owned, rather than a person. The outcome of this depiction is a message that the primary currency of women is their appearance. Men learn to look at women as an object or sight and women are encouraged to present themselves hot and sexy.

This representation creates a climate which normalizes certain expectations and attitudes, and can lead towards violence against women.

Fig. 6: Lynx, 2011

Fig. 7: Dolce & Gabbana

Recent results of Ofsted inspectors showed that sexual harassment is a routine part of the everyday life of school children in the UK. Girls suffer from sexist name-calling, rape jokes, upskirting. Boys share nude pictures like a „collection game“. It found that sex education is underestimated in schools and out of touch with reality. As a result children turn to the social media and the Internet to find information. Internet, social media, advertisement, music videos, movies, etc. is where young children learn about sex.

Jean Kilbourne discussed in her seminar „The Dangerous Ways Ads See Women“;

‚The problem isn't sex, it's the culture's pornographic attitude towards sex, the trivialization of it. Sex is always used to sell. But it is far more graphic and pornographic today than ever before.’

Fig. 8: Tom Ford, 2013

And she goes on;

‘These ads don’t cause violence against women directly but they create a climate in which women are often seen as things, as objects. And certainly, turning a human being into a thing is almost always the first step towards justifying violence against that person.’

(Kilbourne, 2014)

In the last module I created a body of work which was responding to the stereotypical ideals of beauty, perfecting the female body and representation of women as sights. I created unflattering and surreal images of myself to confront the viewer’s gaze.

Fig. 9: Lucie Nechanicka, Pretty for the Camera, 2021

Fig. 10: Lucie Nechanicka, Pretty Boobs, Pretty Ass, 2021

However, in my Final Major Project I would like to voice out an issue which is one of the outcomes of the stereotypical representation of women – street harassment.

I am going to focus on catcalling, groping, upskirting, stalking, etc. I believe these topics deserve more attention, and the consequences need to be viewed in a bigger picture as this leads towards bigger issues such as violence against women.

I have decided to work with other victims as well as share my own story. The idea is to take coloured, documentary photographs of the clothes women wore at the moment of harassment, accompanied by photographs of the place where it happened. These images would be in diptych or perhaps triptych form, if I also add extra simple portraits of each woman. I am planning to title the images by what exactly was said to the women.

The purpose is to present to the viewer that experiencing harassment can happen anytime, anywhere and to anybody. But unfortunately a lot of women are quiet about their experience and simply brush it off because it became so normalized and accepted in our society. Young girls are growing up in an environment where they learn that the best thing to do is to get used to it. Whilst young boys are learning that this sort of behaviour is expected of them.

I am hoping my project will empower those who experienced harassment in public places, and spread the awareness of the danger that seemingly „unharmful“ behaviour can lead towards.

The danger lies in creating the right climate where this behaviour blossoms - by trivializing and accepting it, and passing it on others.

These are artists that I find really inspiring in the way how they respond to the same/similar topic.

The British photographer Sarah Lucas is concerned with misogyny of every day life. Two images of hers sparked up an idea for my project. „The Self Portrait With Fried Eggs“ from 1996, where the fried eggs represent her breasts, is a reflection of how British men sexualize the female body in a vulgar way. Similarly, her other self-portrait „Chicken Knickers“ from 1997, where the chicken represents her vagina, is a darker version of the same subject matter.

Fig. 11: Sarah Lucas, The Self-portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996

Fig. 12: Sarah Lucas, Chicken Knickers,1997

In 2011 Cindy Sherman became a face of MAC, the makeup company of outsiders and artists. She depicted herself in three different ways; as a clown, an unhappy rich woman and a creepily looking young girl. This was an unconventional step for advertising a beauty product, as makeup campaigns commonly use beautiful models to convince women how wonderful the cosmetics will make them look. In my opinion this is a great step forward in showing that makeup can be used for the transformation of self, having fun or just looking different rather than a promise of improving oneself.

Fig. 13: Cindy Sherman, collaboration with MAC cosmetics, 2011

In her project „Hey Baby“ Caroline Tompkins snaps photographs of her catcallers who harassed her on the street. I find her project incredibly powerful because she is confronting them back by turning her lens on them in their act.

Fig. 14: Caroline Tompkins, „Hey Baby“ series, cca. 2011 Fig. 15: Caroline Tompkins, „Hey Baby“ series, cca. 2011 Bibliography Text: Berger, J. (1972), Ways of Seeing, Chapter 3, p. 54 Berger, J. (1972), Ways of Seeing, Chapter 3, p. 64 Forster, S. (2018), Yes, there’s such a thing as a ‘female gaze.’ But it’s not what you think https://medium.com/truly-social/yes-theres-such-a-th ing-as-a-female-gaze-but-it-s-not-what-you-think-d2 7be6fc2fed Jhally, S. (2007), Dreamworld 3: Desire, Sex in Music Videos Guardian, (2021), Sexual harassment is a routine part of life, schoolchildren tell Ofsted https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/jun/10/sexual-harassment-is-a-routine-part-of-life-schoolchildren-tell-ofsted?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Other&fbclid=IwAR2CmYget6qQl4iNjUQMhFg2gY-N4WZE10B7n8PNq8LXxCqtvUbCYaRO84o Kilbourne, J. (2014), The Dangerous Ways Ads See Women https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uy8yLaoWybk&ab_channel=TEDxTalks Figures: Fig. 1: Peter Lely, Portrait of a young woman and child, as Venus and Cupid, 17th century, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4942789 Fig. 2: Dolce & Gabbana, Light Blue https://thescentsofself.com/2012/02/20/dolce-gabbana-light-blue/ Fig. 3: Transformers, 2007 https://femfilm18.wordpress.com/2018/11/15/the-male-gaze-in-transformers-2007/ Fig. 4: Lucie Nechanicka, Untitled, 2020 Fig. 5: Lucie Nechanicka, Untitled, 2020 Fig. 6: Figure 3: Lynx, 2011 https://www.thedrum.com/news/2011/06/29/lucy-pinder-stars-saucy-lynx-web-games Fig. 7: Dolce & Gabbana https://ny.racked.com/2009/6/15/7820739/billboards-sohos-calvin-klein-threesome-is-borderline-pornographi c Fig. 8: Tom Ford, 2013 https://www.marketsmiths.com/2014/badvertising-scent-of-a-woman-tom-fords-va-jay-jay-fragrance-ad/ Fig. 9: Lucie Nechanicka, Pretty for the Camera, 2021 Fig. 10: Lucie Nechanicka, Pretty Boobs, Pretty Ass, 2021 Fig. 11: Sarah Lucas, The Self-portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996 https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lucas-self-portrait-with-fried-eggs-p78447 Fig. 12: Sarah Lucas, Chicken Knickers,1997 https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lucas-chicken-knickers-p78210 Fig. 13: Cindy Sherman, collaboration with MAC cosmetics, 2011 https://www.musingsofamuse.com/2011/07/cindy-sherman-for-mac-collection.html Fig. 14: Caroline Tompkins, „Hey Baby“ series, cca. 2011 Fig. 15: Caroline Tompkins, „Hey Baby“ series, cca. 2011 https://www.juxtapoz.com/news/photography/caroline-tompkins-s-hey-baby/

Comments